My Store

Mr. Bennet's Daughter

Mr. Bennet's Daughter

Couldn't load pickup availability

Buy as part of a ten book bundle and save

Get paperbacks on Amazon

Mrs. Bennet fled from Longbourn with her lover and Jane two months after Elizabeth was born, leaving little Elizabeth behind with Mr. Bennet. Mr. Bennet dedicated his life to raising Elizabeth the best he could. Mr. Bennet had loved Elizabeth dearly from the first time he picked his little girl up and she smiled her baby smile at him, and grabbed at his sideburns.

When Mr. Bingley and Mr. Darcy arrive in the neighborhood, Elizabeth finds herself falling in love with Mr. Darcy. He makes her heart flutter, and he respects her like nobody but her father respects her. What will happen when Elizabeth’s long departed mother returns to Meryton after being absent for twenty years?

A heartwarming and romantic novel about family, love and forgiveness from the author of Mr. Collins’s Widow.

Share

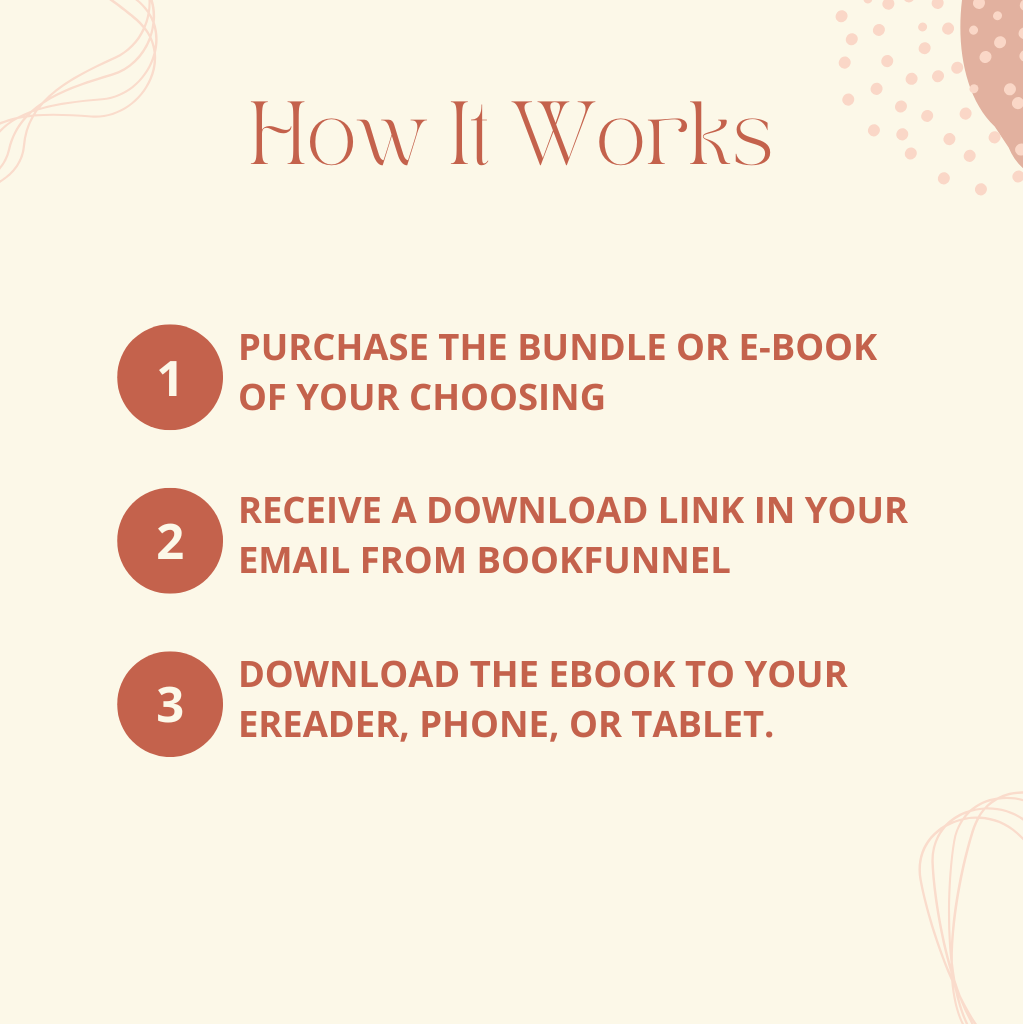

FAQ: HOW WILL I GET MY BOOK

FAQ: HOW WILL I GET MY BOOK

E-Books will be delivered via a download link in an email from our delivery partner Bookfunnel.

Make sure you check your promotions and spam folders if you do not receive an email within a minute.

FAQ: HOW WILL I BE ABLE TO READ MY BOOK

FAQ: HOW WILL I BE ABLE TO READ MY BOOK

You will be able to read this on any Ebook Reader (Kindle, Nook or Kobo) and on your computer, tablet or phone. The email from Bookfunnel with the download link will include easy to follow instructions for entering the book into e-reader libaries.

FAQ: REFUNDS

FAQ: REFUNDS

Digital Products have a 30 day refund window. I really don't want to keep your money if you don't think that I gave you something worthwhile. If you hate what you are reading, use the contact form to send me a message, including your name and order number and add a sentence or two about why you disliked the books, and I'll send you your money back.

READ A SAMPLE

READ A SAMPLE

Mr. Bennet of Longbourn sat in a corner of the Meryton assembly room, ignoring the aching violin, the smell of wine and poorly cooked fancy hors d’oeuvre from the buffet, and the crowd of men in the side room playing at cards for stakes of a half crown, and instead he engaged in the quite unfashionable, and frankly unneighborly, behavior of openly reading a book at a ball.

Not even a novel! But a text upon the proper ordering of hypothetical societies and the true nature of justice. Written in Greek, with gold letters stenciled upon the front that only a very few of his dear neighbors could hope to interpret.

In the actual fact Mr. Bennet paid less than half his attention to his slightly musty book — he had read Plato, all of Plato, even the incomprehensible dialogues about the nature of “the one”, and whether it be divisible or not, more than twice.

He rather thought he should have brought with him the tome he had open on his desk at home, upon the (rarely) exciting topic of crop rotation. However, as he’d gone to pick it up, for his evening reading at the noisy and drafty ball, his beloved and familiar Plato, placed on Elizabeth’s desk as she had been reading a piece from The Republic the previous day, and not returned it yet to the shelf, caught his eye.

And so the useful though dull text was replaced by The Republic.

But Mr. Bennet did not pay a great deal of attention at present to his book, even though it was The Republic. Rather his eyes were caught by two points of interest. The one was his purpose at being present in these assembly rooms past ten o’clock when there was a well laid fire that could be kept merrily roaring in his drawing room, while Lizzy sat across from him and read her own book or sewed, or while they talked or played a game of chess — she had started to beat him often over the past year.

Elizabeth, in a preference that was as entirely rational as it was entirely unfortunate, liked to attend balls and dance.

At this moment she was dancing a second set with that Bingley fellow who had just taken Netherfield.

Mr. Bennet had no woman to whom he would entrust his beloved daughter. He trusted Elizabeth’s good sense, he trusted Elizabeth’s morals, and he trusted her affectionate emotions. But she was still the daughter of a woman who had run off within two months of the birth of her second child.

He should be there, just to make sure she was not being taken in by charming men — though Mr. Bennet had sufficient time and self-awareness to know that Mr. Yates’s superiority, such as it had been, was not in the matter of being more charming than Mr. Bennet himself.

Besides his Elizabeth was in every way superior to Mr. Bennet’s former wife.

However, he still was determined to keep an eye on her in society.

Mr. Bennet had in general arranged his life to support his daughter ever since she had been born. He had troubled himself to take the estate under better regulation, and to closely limit their spending so he could set aside a substantial dowry for her, he had taken great pains with her education — though it was decidedly unconventional, and perhaps masculine in its tendencies, and he would ensure she was properly chaperoned, by the one person he would trust with his daughter’s care, himself, when she was in society.

Every month Mr. Bennet presented himself at the Assembly balls, and when his neighbors found money and the desire to hold a ball of their own, he was there likewise, sitting in the corner, talking to his acquaintances or reading. And every year since Lizzy had come out when she was seventeen he had thrown a modest private ball of his own at Longbourn.

The one thing he had not yet done was give Lizzy a London season. His girl professed little interest in one, and Mr. Bennet was not particularly eager to see her surrounded by the wealthy society men in Town.

Of course, Mr. Yates, who had married Mrs. Bennet the day the divorce articles were passed through parliament, had not been a rich society man, but rather the modest law clerk of modest Mr. Gardiner, Mrs. Bennet’s father.

Mr. Bennet still had a habit of thought of insulting Mr. Yates in his mind, but in truth he bore very little animus towards him.

It had taken the passage of more than a year for Mr. Bennet’s righteous rage to quiet, but not only had his marriage with Frances Gardiner been a terrible mistake (that he had determined before the first year of marriage was complete, and long before Mr. Yates had even arrived in Meryton), its dissolution produced a substantial improvement in the situation and happiness of all involved, though not in their reputations.

He had been unhappy with Mrs. Bennet. He had made Mrs. Bennet unhappy.

Now he was happy, far happier without her than he could have been with her. And what few reports he had gained of the former Mrs. Bennet since she became Mrs. Yates, claimed she was happy as well, despite the fact that Mr. Yates was a man substantially inferior in consequence to Mr. Bennet.

Mr. Bennet thought it would be rather strange for a philosopher to rail against actions and events which added to the happiness of all the principal parties involved merely because those actions included adultery and his cuckolding.

Still, Mr. Bennet did not want to go to London.

And he did not particularly want Elizabeth to meet the rich men, dissolute men of the capitol. Men who would just see her person and her dowry — those modest enough to be tempted by the fifteen thousand he’d set aside for her — but never Elizabeth’s chief glory: her mind and her spirit.

Mr. Bingley and his guest were society sorts of men.

Mr. Bingley seemed like a nice sort of society man. He was well educated. Cambridge he’d said when asked, instead of Bennet’s own Oxford. Still, university educated, for the good it did him.

A particularly handsome face.

A fact which Elizabeth noted when Mr. Bennet permitted him to be introduced to Lizzy when Mr. Bingley returned Mr. Bennet’s call upon him a week after his arrival in the neighborhood.

Mr. Bennet knew Lizzy was, in the natural way of any girl who led in the small society of her village, assessing the newcomer for his suitability as a possible husband. After all, while single men of great fortune may or may not be in want of a wife, every single girl of twenty years was curious about the married state — even the ones who disclaimed any interest in ever leaving their dear Papa.

Mr. Bennet was aware enough of how these things went to not be particularly opposed to the notion: Netherfield was close enough that Lizzy and Mr. Bennet would be able to visit every day should she marry Mr. Bingley, which was a matter Mr. Bennet would strongly prefer in any match for Elizabeth. But it wasn’t as though that was particularly important. Should Elizabeth move a great distance away, he would overcome his antipathy to travel and hire a steward so he could visit her regularly.

What always mattered to Mr. Bennet was that when, or if perhaps, Elizabeth married, she married happily and well.

Mr. Bennet’s eye also followed Mr. Bingley’s friend. Poor, sad, ball hating, and likely shy Mr. Darcy.

Mr. Bennet could almost precisely recognize himself in the poor man, in the way he’d been lost at the balls he attended in the neighborhood during the first months after he’d returned from his continuing studies at university following the death of his father.

He’d known that as a substantial landowner it was his duty to be sociable and attend the balls in the community, he also had known he was supposed to dance, and natter about with the women, and he was supposed to talk about manly subjects like field drainage and fox hunting with the other landowners.

It had been a terrible time, the time during which he made that greatest mistake of his life: Seeing Miss Frances Gardiner, developing an instant passion for her appearance, and then making his interest very obvious to her and her mother.

He had been very much a fool.

Mr. Bennet studied Mr. Darcy further from the corner of his eye. From the turn of the young gentleman’s mouth, Mr. Bennet suspected that as much as the gentleman hated the social obligation of being at a ball, Mr. Darcy was simultaneously of a less sociable disposition amongst strangers, and made of sterner stuff than Mr. Bennet had been.

There was something about that man’s mouth. When he married, he would not make a choice in blithe confidence of its brilliance that he would regret within a six month.

As the course of the ball continued, Mr. Bennet saw as Mr. Darcy’s pacing become increasingly restless, as his frown grew deeper, and his manners more imperious and less polite. As a shut-in by temperament, Mr. Bennet understood very well. The hour was almost eleven. Any sensible gentleman would be in bed because it was easier to read and conduct real business by sunlight.

It was past Mr. Darcy’s bedtime, and what patience he had for the nonsense of his neighbors was gone.

But also there was something else. Though he did not wear any black armband, Mr. Darcy’s mood was a little like that of a grieving man pushed too fast into company. Or maybe not that, but there was some thought that occupied his mind when he wasn’t busying himself with sneering at the ill-dressed (by his standards only) local yokels.

The poor boy was by now in quite an unhappy temper. Mr. Bennet looked down at the Plato propped on his knee and sighed a little mournfully. It was time for him to do a deed of kindness, and to see if he’d assessed from his watching Mr. Darcy’s character correctly.

He walked up to the young gentleman and without speaking handed him his book.

The young man mechanically took the book, and then blinked at the cover. “Why do you hand me this?”

“It is clear from your manner that you need a book much more than I do.”

The young man looked down at his hands. He stared blankly at the Greek lettering for a long moment and then shook his head. “The Republic? What is it that you think I need Plato for?”

“For the consolations of philosophy.” Mr. Bennet grinned. “Fine education. I thought you would have had one from your look, though I dare say your Greek is a tad rusty as you required an effort to read the title.”

This drew a quick bark of a laugh, which was rather unexpected, as Mr. Bennet had half expected his approach to the haughty young man to be haughtily and heartily rebuffed.

From the bemused look on his face, Mr. Bennet suspected that the tall youth was also surprised by his laugh. “You pegged me neatly to the board — I was at one time one of those who did not let a day go by without waylaying some acquaintance with effusions upon the beauty of blessed Greece, and the greatness that was grand Rome — I fancied myself something of a philosopher.”

He shook his head a little sadly, brushing his hands over the gold leaf letters of the title: Πολιτεία του Πλάτωνα. The young man opened the book to a random page in the middle and smiled at it. “Not since my father died. I found myself busy for a while, and then…”

Mr. Bennet nodded. “Even if raised to the position, managing an estate and the responsibilities, it takes time to accustom oneself to the duties.”

He smiled, still flipping carefully through the text. “Very true. There were two or three years when I found myself without time for myself. I wished to see everything done carefully, properly, and rightly, the way I thought my father would have managed it… I do not intend a boast by saying this, but my estate, Pemberley, is far too large to even attempt to manage without the help of my steward, but I required several years for the lesson to be learned. And by the time I had achieved a balance… as you said both my Greek and my Latin were rusty…”

The two men looked at each other, both with rather sad smiles. “We both lost something in taking command of our estates,” Mr. Bennet said. “I have always castigated myself, for I was quite the opposite of you at first, and it was only after a period of years, and… harsh lessons, that I found sufficient reason to care for business matters and take them into hand. However, I never lost my love for scholarship and those obsessions of university days, and…” Mr. Bennet tapped the book in the young gentleman’s hand, “my philosophy and my studies would be a severer loss than anything in my life but my daughter.”

“So what again was it,” the gentleman said, after looking up from puzzling out some lines of the Republic, “that you think I should do with The Republic? — this is quite embarrassing, We bowed to each other when I was presented to the company here, but I confess, I have completely lost memory of your name.”

Mr. Bennet laughed. “Mr. Bennet of Longbourn, Hertfordshire. At your service.”

“Mr. Darcy, of Pemberley, in Derbyshire. At your service.”

The two gentlemen bowed to each other.

Fans of Abigail Reynolds will really enjoy this book. A very interesting take on Our Dear Couple, with Mr Bennet being a helicopter parent after his wife ran away with her lover and toddler Jane. Lizzy is bright and sparkling, and Darcy falls in love with her mind and spirit, which is my absolute favorite trope. The plot is reminiscent of Gaskell's North & South, if you can picture Darcy learning philosophy from Mr. Bennet the way Mr. Rochester learned from Mr. Hale. Again, major favorite, I love all the literary references in Underwood's books.